Comparing DSA and the Belgian Workers' Party

They are very different organisations. We can't build them both...

Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) and the Belgian Workers Party (PTB) are often cited as sources of inspiration for the new left party.

There is good reason for this. They’re both socialist organisations that have enjoyed growth and success in recent years while balancing electoral and base building work, nurturing internal democracy and sticking to their principles.

But despite being cited in tandem, they are very different organisations. We cannot build both DSA and the PTB. In short:

DSA is a broad left, highly decentralised socialist organisation that is transparent, pluralistic and emphasises democratic process where every member has power.

The PTB is an ideological aligned, tightly controlled political party that is opaque, single-faction and emphasises democratic outcomes where only cadre members have power.

Hopefully this post is an easy to digest, top-line comparison of the two organisations, focussing on their differences rather than similarities.

It’s drawing from a soon-to-be-published research project for the Rosa Luxembourg Stifung where I interview twenty leaders, members and former members from the DSA and PTB. There’ll be lots more to say in the final report, so I’ve tried to limit this to descriptive comparison rather than analysis of what works and what we should replicate.

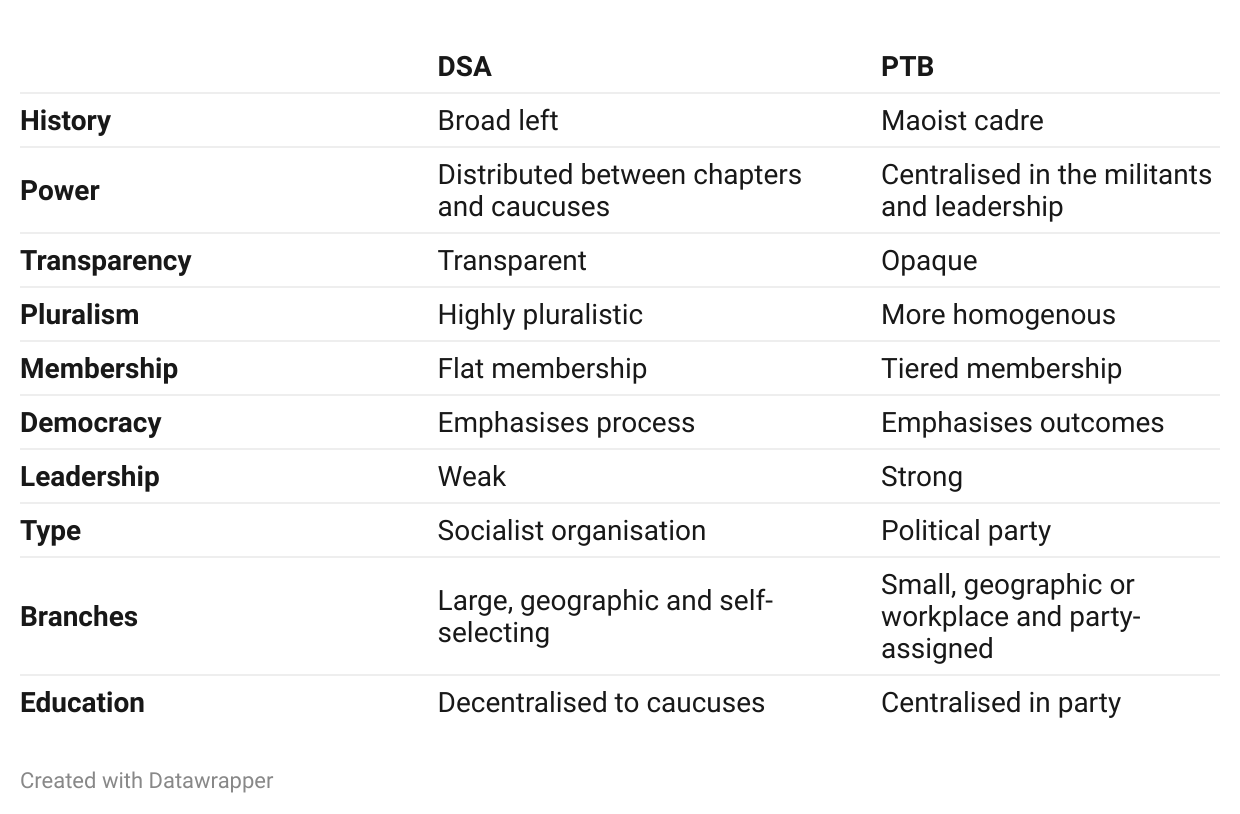

If you don’t want to read the whole thing, here’s a nice and probably controversial table:

1. DSA has always been broad left, the PTB has Maoist origins

DSA has always been a broad left organisation. Formed as a merger of the Democratic Socialist Organising Committee (DSOC) and the New American Movement (NAM) in 1982, the organisation has always housed multiple tendencies, focussed on mass membership rather than cadre building and has relatively loose structures.

The PTB originated as a Maoist organisation and opened up in 2008. Originally a coalition of Maoist students and workers in the docks and car factories in 1979, the PTB remained a small, disciplined, high-commitment cadre organisation for decades. At their congress in 2008, the party opened up its structures to members and supporters with less ideological unity and lower commitment levels, but who still wanted to support the party.

2. DSA is decentralised, the PTB is centralised

DSA has a radically decentralised organisational structure where chapters are the site of most work and power is held in the 12+ ideological caucuses, who largely control the elections to the National Political Committee (NPC) and the composition of national working groups.

Decentralisation is so pronounced that DSA members joke about how little power the NPC has and some successful chapters like New York DSA rarely engage with national structures.

The PTB has a highly centralised structure where power is held by the leadership and militant layer. Democratic centralism is practised: internal debates happen, but once decisions are made they become the party line and publicly, members stick to it. There are no competing factions observable from the outside. The PTB’s congress takes place every 3 - 4 years and is the culmination of a year long strategy process involving all PTB militants.

Geographical context matters here. Belgium is 10 million people, smaller than London. The USA is 340 million across a continent. The PTB’s tight coordination is feasible partly because you can drive across the country in hours. Whether such centralisation works at UK or US scale is an open question.

3. DSA is transparent, the PTB is opaque

DSA is a transparent organisation. Minutes, membership numbers and event reports are shared widely. Fights at convention spill onto Twitter. Interview ten different DSA members and you’ll get ten different stories about what the organisation is and how it should be.

The PTB is an opaque organisation. Internal democracy and deliberation is kept secret. They don’t publish membership and branch numbers. Interview their members and they’ll likely refer you to agreed congress documents.

4. DSA has pluralist factions, the PTB has a united cadre

DSA has as many as twelve publicly declared caucuses which any member can join. These range from Bread and Roses (Hal Draper-influenced) to Groundwork (eco-socialist) to Red Star (Marxist-Leninist). They have differing ideological positions and compete for control of national working groups, local chapters and the National Political Committee.

PTB has no declared factions perceptible from outside. Deliberation happens at congresses and in the year-long process running up to them, but once decisions are made, discipline holds and from the outside, the militant layer seems remarkably united.

5. DSA has a flat membership structure, the PTB has tiers

DSA has essentially one tier of membership. If you pay dues (around $5-10 monthly), you’re a member. There are no formal expectations or obligations. In practice there’s enormous variation - paper members who do nothing, active members, leaders, national committee members - but this isn’t formalised.

The PTB has three formalised tiers. Supporters pay €20 yearly with no obligations - they’re a “fishing lake” for recruitment. Members pay €5 monthly, attend monthly base group meetings and are expected to be active. Militants have completed cadre training, agree with party statutes, take on higher responsibilities, and can vote at congress. Only militants elect national leadership.

6. DSA has highly democratic processes, the PTB focusses on democratic outcomes

DSA has highly democratic processes. Conventions every two years, chapter meetings where members decide priorities, competitive elections at every level. As one DSA member said: “This brings problems - faction fighting, lack of discipline, chaos - but we have thousands of people truly loyal to DSA who put in enormous time as volunteers precisely because there’s so much feeling of member control.” However, DSA’s democratic processes don’t always produce democratic outcomes and clear strategic direction. This is reflected in the organisation’s struggle to reorient nationally, and that resolutions are often passed at congress without the resources to implement them.

PTB has clearer democratic outcomes. Supporters can’t vote. Members vote only in base groups. Militants vote at congress. But decisions, once made, seem to have clearer mandates and implementation. When the party decides on a national campaign, the entire apparatus moves, for better or worse. The national leadership are clearly accountable to the militants. Each congress document outlines a coherent plan that the leadership are responsible for implementing.

7. DSA has weak leadership, the PTB has strong leadership

The DSA’s National Political Committee (NPS) has formal power but until recently lacked information or capacity to exercise it effectively. The DSA’s Democracy Commission found the national organisation was “blind” to chapter activities. Recent reforms are trying to fix this: expanding the NPC by 30% (more hands on deck, easier for independents to get elected), creating central archive requirements for chapter minutes and resolutions, and requiring the NPC to lead national discussions quarterly. But chapters remain largely autonomous in practice, and national staffing has been inadequate to follow through on national campaigns and congress motions.

The PTB’s leadership holds both formal power and information through more centralised structures. Decisions flow from congress to national leadership to provincial coordination to base groups. There’s clear accountability upward and direction downward. There is a strong leader’s office and bureaucracy built around Peter Mertens, the General Secretary. This allows sustained campaigns and institutional memory, though it undoubtedly embeds the power and position of the leadership.

8. DSA is a socialist organisation, the PTB is a political party

DSA is a socialist organisation, not a registered political party. It doesn’t run candidates as “DSA” - instead it endorses candidates who run as Democrats or independents. This strategy emerged because the US two-party system and ballot access laws make third parties extremely difficult. Some factions advocate for a “clean break” with the Democrats and forming a real party, but it’s unlikely soon. The major problem: DSA candidates aren’t formally accountable to DSA at all. They make no binding commitments beyond accepting the endorsement.

The PTB is a registered political party that runs its own candidates. Elected officials are party members first, bound by democratic centralism. They can be recalled if they break from the party line. However, this also means the PTB face the contradictions of taking power: not wanting to enter government before having power to enact transition, but being offered local government positions where their hands are tied by budget constraints and national policy.

9. DSA has city-wide chapters, the PTB has small base groups

DSA chapters are large, city-wide units that function as the primary site of activity and decision-making. New York DSA has thousands of members, Chicago DSA likewise. Members self-select and join the chapter they wish. Within these chapters, work is organised through working groups and campaign committees that members join based on interest. Chapter meetings, when they happen, can have hundreds attending. Chapters operate with significant autonomy, each with its own bylaws and priorities.

PTB base groups are kept deliberately small - between 6 and 13 members maximum. As one member explained: “If a base group has more than 10 members, we try to split it up because otherwise it’s really difficult to have a good discussion with everybody.” These groups meet monthly for two hours: half for political education (either on current events or organising skills), half for planning local action.

Base groups are organised by neighbourhood or workplace, and you’re assigned to one - you don’t choose. If your local group is full, you might be assigned to a nearby one. This creates coverage across territory rather than clustering around issues or personalities. Multiple base groups in the same area coordinate through section meetings, and all base groups receive the same political education materials and campaign priorities each month.

11. DSA political education is caucus-run, the PTB’s is party-run

DSA has no national political education program. The DSA is a big tent containing social democrats, anarchists, Trotskyists, Marxist-Leninists, Maoists and more. One organiser explained: “We would have to find politically neutral political pieces... what would that even mean?” So political education has been effectively outsourced to caucuses, who educate members in divergent and often self-reinforcing ideologies.

PTB has centralised cadre schools. To become a militant, you must complete training where “you have to know the statutes and you need to agree with the statutes.” Base groups also receive monthly political education, alternating between analysis of current conditions and organising skills.

Interesting read, thanks Joe! I came into this expecting to favour the DSA, but in many ways - when our challenge is to take power and transform the world - it seems that PTB is more effective.

Coordinating campaigns, socialist political education, and actively organising members; I think these are the most important tasks of a party and PTB seems to be leading the way on this?

PS: The two organisations also have a very different class basis.